My lecturer bounded into class, replete with a Sex-Pistols-esque mohawk encircled by a shaved-and-tattooed skull. This was not theology, nor was it public relations.

This was media studies.

As a 17-year-old, first-year student, I was taken aback by this educator’s appearance. Used to clean-cut secondary school teachers, this man’s look was so different. And so was his teaching.

He encouraged vigorous debate, showcased a range of films and introduced me to a cocktail of thinkers — from Plato to Freud to Baudrillard.

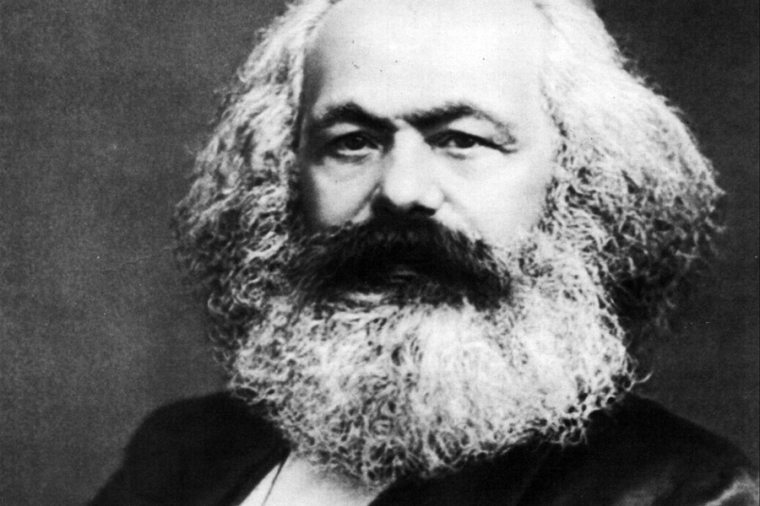

One day, I went into my professor’s office, seeking ideas for an upcoming essay. 25 minutes later, I walked out — my head brimming with ideas, and my hands clutching his copy of Karl Marx’s The Communist Manifesto.

I read that book cover-to-cover. Like many of my classmates, I became convinced that the core approaches of Marx (apart from his fairly pronounced atheism) was correct.

Over the years, that view has definitely softened — I’ve grown out of my wanna-be Marxist stage. But I am grateful to that professor for introducing me to Marx – because Marx taught me four important lessons about following Jesus.

1. Use Your Brain.

Karl Marx was many things – political activist, journalist, socialist — but he was also a deep-thinking philosopher.

After being banned from Germany and Belgium, Marx took his family to London. He lived there from 1849 till the end of his life — and spent most his time in the reading rooms of the British Museums.

Here, Marx blended the concepts of Hegelian philosophy with the insights of his friend Friedrich Engels and with the economic history of English land ownership. For over 10 years, Marx would read, study and write — eventually producing his magnum opus — Das Kapital, a three-volume epic.

Karl Marx thought deeply about his philosophy, and sought to ground it on eons of data — all before the days of digital computing power.

As I read Marx, I realised that things of life that mattered deeply deserved deep thought. Marx had done so with economics and government.

Yet, much of my experience with faith had fallen short of the critical levels. I had not been challenged to think deeply about my beliefs, or been taught how to wrestle with issues, considering both sides of an argument, and to develop my own conclusions grounded on belief.

Karl Marx taught me to think deeply about the stuff that matters. As the Christian faith proclaims a focus on the grand story of everything, my reading of Marx urged me to engage even deeper about my faith – and begin the oft-difficult process of thinking and reading at a deeper level.

2. Care for the poor.

One of the core tenants on Marx’s philosophy is his scathing critique of the exploitation of the working class.

In Das Kapital, he writes,

Capitalist production, therefore, develops technology, and the combining together of various processes into a social whole, only by sapping the original sources of all wealth — the soil and the labourer.

Instead of viewing the working class — which in Marx’s time lived in incredibly impoverished situations — as a economic mass of labour, Karl Marx sought to offer them a new world of equality. No-one would own anyone — no-one would be transformed into capital by the transaction of input-to-wage.

This came from Marx’s observations of the suffering of the poor. Instead of merely seeking to describe the world through his philosophy, Karl Marx sought to change it.

At the time, my understanding of Christianity was primarily about avoiding sin and living well. Sin, in my understanding, was about the bad things I could do to myself. This was a strongly individualistic approach — and, to be honest, I was much more familiar with the words of Paul, than I was with the words of Jesus.

Jesus, in my early days of Christianity, was someone who had died for me – and it didn’t really matter what he had said. He was the sacrifice, not a teacher.

And then I re-read Matthew 5–7 — Jesus’ series of sermons about how to live well. I was stunned.

Here, Jesus is teaching a way of life that does not seek to describe the world – but to utterly transform it. Where Plato and the Greek philosophers promoted stability — Jesus is preaching a gospel of upheaval.

Jesus urges people to leave in the middle of church services to reconcile with friends and family. He commands his hearers to pursue forgiveness instead of revenge. He revolutionises prayer, giving, promising and living.

And the primary audience he is preaching to? The poor. He honours them — and explains how they are specially cared for. They are central in his message of good news.

Here, there is no dichotomy between social action and moral living. Teaching on lust and anger cosy up with charity and social care.

My understanding of Jesus was far too small. Reading Marx helped me see that as revolutionary as Marx’s manifesto was — Jesus was more so.

3. The function of power.

Behind much of Marx’s writing is a focus on power. Capitalism exists, according to Marx, to generate as much value as possible for the individual. To do this, the wealthy must live by the rule of:

“Unlimited exploitation of cheap labour-power is the sole foundation of their power to compete.”

Do you see what Marx is saying? The wealthy have the power, to turn the power of the labourer into a commodity — giving the wealthy more power to compete, more power to produce, more power to consume.

Marx saw much of life as a battle of power — and the effect of what this power does to people. These power structures — the relationships of power that seem normal to us — actually undergirded a great inequality to our society.

This power seemed normal — but to Marx it was profoundly dehumanising. This power turned a human being into a labour input — valued only by how much they could produce — and for what cost.

A few thousand years before Marx, the prophets did the same thing. They spoke scathing words to the ears of the powerful — showing them how their actions were creating normal structures — that were profoundly abnormal.

The prophet Amos, a manager of shepherds, ventured to the powerful in the land of Israel, and shouted words of critique to their deaf ears. He says,

“You levy a straw tax on the poor

and impose a tax on their grain.

Therefore, though you have built stone mansions,

you will not live in them;

though you have planted lush vineyards,

you will not drink their wine.

For I know how many are your offenses

and how great your sins.”

Imagine this. The rich hearing these words — and agreeing. Yes, we tax the poor. So what!? Everyone does.

But Amos talks about how this abuse of power is sin.

What is the result of these taxes? Your stone mansions, and your lush vineyards. But you will not enjoy them. God cannot stand this abuse of power.

Similarly, the early church flipped the usual power structures by seeking to ignore the class system that was rife in the Graeco-Roman world.

Paul writes, “There is no longer Jew or Gentile, slave or free, male and female. For you are all one in Christ Jesus.”

Imagine this — slaves sitting down with their owners, to share communion. The owner joining hands in prayer with his slave. The Jew and the Roman kneeling in prayer together.

The Christians took this idea so seriously that in the year 218 they elected Callistus as the Bishop of Rome — the highest office in the Christian church. His prior role?

A slave.

Marx woke me up to the role of power in society. But then the Scriptures pointed out that they had been screaming this message for millennia – but my ears had been too deaf to hear.

The heart problem.

The ideas of Karl Marx grabbed me. But when I looked to the world to the best models of his ideas being lived out — I saw a huge short-fall.

The USSR – one of the earliest adopters of Marx’s beliefs — began with a painful revolution of the working class. Under Communism — the equality of all would finally become a reality.

Instead, corruption reigned supreme. Anyone who was perceived to be different was suspect — and often tried, imprisoned or executed. Nepotism ruled. The new rich got richer. The poor stayed poor.

Karl Marx aimed to change the world through philosophy and revolution. And history tells us that philosophy and revolution are not enough. The heart runs deeper than words and politics.

Given a perfect world — the greed, lust, anger and desire in my heart will ruin it. No amount of political power, legislation or revolution will fix that.

When God speaks through the prophet Ezekiel, he proposes a bigger revolution than Marx could ever imagine.

He says,

I will give you a new heart and put a new spirit in you; I will remove from you your heart of stone and give you a heart of flesh. And I will put my Spirit in you and move you to follow my decrees and be careful to keep my laws. Then you will live in the land I gave your ancestors; you will be my people, and I will be your God.

God promises what Marx never could.

Reading Marx taught me that if our problems really are as deep as they seem — and effecting all — then we need deep and wide solutions, that are bigger than us. We require a heart change.

Marx could always change my mind. But he could never change my heart.

I’m thankful to my lecturer for introducing me to Karl Marx. I’m thankful to Karl Marx for providing me with mental gymnastics, for introducing me to the role of power abuse and urging me to consider the poor.

But – I’m even more thankful that his answers come up short. And that in reading Marx, I was encouraged even more to read Jesus — and discover what a true, life-changing revolution could look like.

First published October 3, 2017 on www.jeremysuisted.com.

Jeremy Suisted is from Cambridge NZ a Creative Consultant and was once voted in the Top Six Waikato’s Hottest Muffin Bakers.