Michael English was a certified big shot in the Christian music scene of the early 90's. The man was an acclaimed gospel singer and in 1994 picked up four Dove Awards off the back of a national tour. He was the top Christian artist at the time and had it made.

But on May the 6th of the same year, the word 'scandal' became forever attached to his name as it emerged that he had been involved in an affair. The affair had resulted in pregnancy. The squeaky clean image was gone.

English was instantly shunned by the Christian community, his music removed from stores and his songs taken off the radio. He slipped into bankruptcy and drug addiction and nearly lost his life to an overdose. The man was clearly no longer a good representative of Christianity after such a faux pas.

But it turns out that these days you'll see him back in front of a Christian audience again. You see, he sorted it out. Now that he's through all that mess his albums are selling and he's back on Christian family programming talking about his turnaround and giving his testimony. His story is dramatic and tells of God's grace. His life looks good again—a new wife, a new baby, a second chance at his career. It's all feel-good stuff. It has a happy ending. His story is now about victory. And maybe that's the problem.

In church everybody loves a finished story.

We love to marvel at the stories of the poor souls who have fallen to drug addictions only to find Jesus, then have Jesus pull them out of their drug addictions so that they can appear on Shine TV and talk about the faithfulness of God. We have lots of time to hear about the back-slidden Christians that saw the light and snapped out of it back into enlightenment with the rest of us. We give lots of air time to the stories of suffering that contain a happy ending. Anything that serve as a good intro for a praise number.

But those with unresolved tensions are awkward.

Our strange little subculture often likes to keep uncomfortable truths quiet and implicitly send out the message that you're only worth listening to if you've got it all together. Keep it feel-good, keep it to things we can applaud, keep it to the uncomplicated. But that makes life hard for every single one of us, because we're all unresolved little stories in our own way.

None of us are finished, vacuum sealed, neat little testimony brochures with all of our contents in order. And if we're getting the message that we're only acceptable if we're okay then we're being set up for a life of keeping up appearances while living with deep shame as we realise that it isn't the real us.

Whakama

Pre-European Maori culture used to acknowledge shame out loud. Whakama was understood as deep shame and embarrassment brought on by wrong doing, seen in the light of the effect it had on the larger community. Irresponsible actions may have resulted in shame for the whanau, hapu or iwi and so the offenders may experience isolation or withdrawal from the group for a time.

Today, largely due to the influence of Western individualism it has changed significantly, but individuals may experience whakama because of unemployment or lack of education. In both eras it has often led to low self-esteem and suicide.

Hearing about this aspect of the culture may appear harsh to us as if it lacks understanding. But it doesn't sound that foreign to me. It seems to be the pattern for fallen church leaders and those in positions in influence doesn't it? We make sure they're stripped of their stages and disciplined. We back up these actions by quoting Paul, saying that leaders should be "above reproach" and if someone in these roles is guilty of wrong doing then the whakama is laid on heavy. This can only send out messages of "If you stuff it up, you're gone!"

The scary thing is that we are all weak. We are all capable of being the next Michael English. We all have parts of ourselves and failures that we are scared will result in some sort of social isolation. We cast judgement on ourselves, knowing that if we were vulnerable about these things, it might be too much for people. We would be unacceptable.

We all carry whakama within ourselves. It's a sobering thought to consider that the NZRU might understand grace and restoration better than the church when looking at their commitment to Zac Guildford in light of his recent "falls from grace".

Telling the story differently

The narrative of Genesis 3 and 'the Fall' has often been described solely in terms of an act of disobedience and then a change in the cosmos; Adam and Eve eat the apple and then sin enters the world. But maybe there is more going on here. Maybe what's going on is a profound change to the way we know things. Human beings in this chapter begin knowing how to perceive the world from a deep relationship with God, an open, vulnerable and naked intimacy with their Creator and each other.

They swap this for self-reliance. For a world in which they decide what is right and wrong, good and evil, acceptable and unacceptable.

We now decide the categories. Some people are now righteous, and some unrighteous. And unfortunately we are now victims of our own thinking, knowing all too well that we do not and cannot live up to these ideals. Self-inflicted whakama. And as a result we cannot stand the intensity of being known truly for who we are, and so we cover ourselves up.

But do you want to know what the real scandal is? God Himself experiences social isolation. God is found to be unacceptable to these human categories. Our whole system of judging the world by our own terms is imploded. He is hung naked from a tree. Jesus becomes whakama so that we can stop hiding in the bushes.

I want to stand with the doubters, the addicts, the screw ups, the people who just can't get their act together. I want to stand with the munters, the embarrassments and the failures. I want us all to stand and marvel at the one who was, thank God, perfect on our behalf, because we can't manage it no matter how hard we try. He is our righteousness and we are being made like Him.

This is very good news.

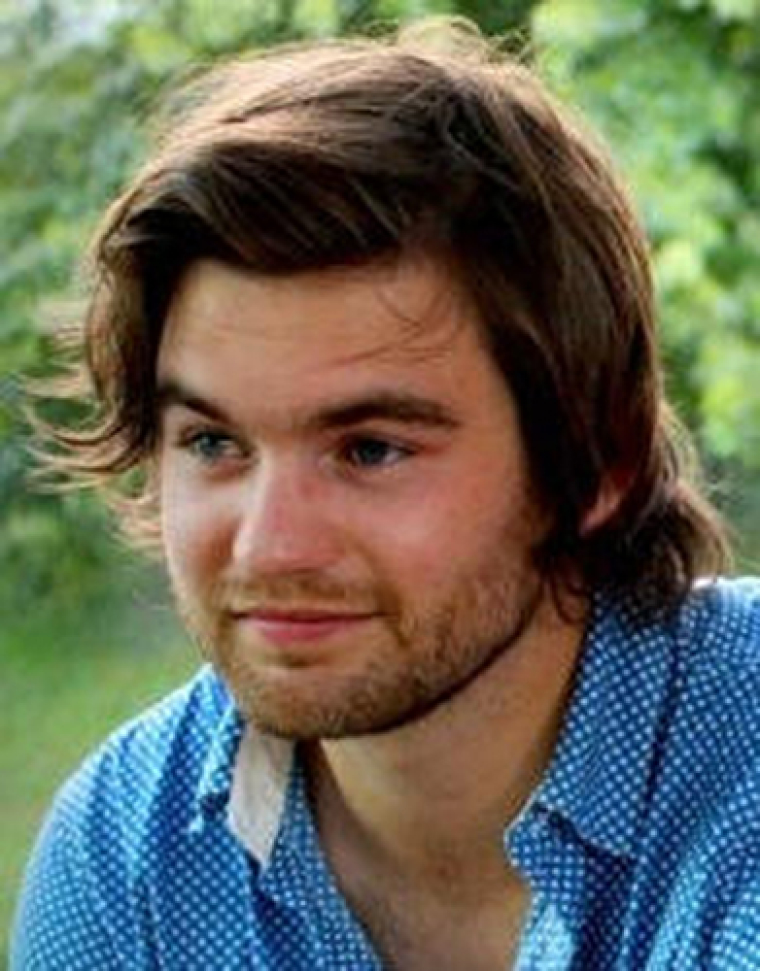

Sam Burrows previous articles may be viewed at www.pressserviceinternational.org/sam-burrows.html