I spent my early teens, my 'awkward years' in England. As if puberty wasn't bad enough already, I had the added discomfort of sporting a southern English accent, living with the pressure of trying to be good at football and being exposed to way too much garage music.

I was there to watch the nation imitate every single one of David Beckham's haircuts, endure the cult of the Spice Girls and went through the obligatory S Club 7 phase (I'm still in love with Hannah). I had to learn to communicate with "birds" using colloquialisms such as "You're well fit" and I had to accept that Craig David was a part of my reality no matter how much I tried to pretend it wasn't true.

Needless to say, when I arrived back on native soil, it felt like a holiday had begun.

But having such formative years outside of New Zealand culture meant that I then inevitably began to become preoccupied by identifying what being a Kiwi actually meant. I developed a paranoia that I was simply an indistinctive child of the West, with no real home or anchor, and that my childhood enduring the hard knocks of Upper Hutt counted for nothing.

So what does it mean to be a kiwi? What sort of country are we? Do I fit?

Firm ideas around us?

Because of these burning questions, I'm always intensely interested in what is reported to be firm ideas around this. An article published in the Herald last week described the beloved Wilson Whineray as a "symbol of all that's good about New Zealand" in being "…granitic in quality, unchanging over the years, a trifle amused, mildly sceptical, self-reliant, not a loner but not necessarily a joiner."

I am intrigued by these adjectives. I like the idea of being a self-reliant loner, but that's probably because I don't really like people.

But this description is still incredibly ambiguous. Mildly sceptical? A trifle amused? What is that getting at? In order to get a grip on what is really behind these different pictures and myths of New Zealand I've realised I needed to get to work and research.

It seems to be becoming increasingly difficult to tell what we truly are, and what is just absorbed global culture. It turns out I'm not the only one with these questions and concerns. It seems that we are all at least a little bit conscious that the New Zealand identity is fragile and needing further incubation before it can hold its own in the wider world. Maybe this identity crisis that I feel is something that we actually need to consider at a national level.

James Belich

Author, James Belich is well aware of this tension, and suggests that we are in fact a very unique window of time in the history of our country. He argues that having only just shrugged off our post-colonial "Britons of the South" label, we appear to be marching full steam ahead into a complete embrace of the global environment.

He writes, "As New Zealand cultural and economic maturity gets belatedly to its own feet, there is a chance that it will be washed away or made redundant by globalising tides. This is one of the many challenges brought by the era of decolonisation, whose midst is the present. Our chances of meeting them should improve if we take a clearer look at our past." I think he's on the money. There is a real danger that much of who we are could be lost in the age of the internet if we don't decide what is most important to us as a country and make a point of embedding it into the fabric of who we are as we move forward.

This globalising tide that Belich speaks of is not an attractive prospect to me. It's a tsunami of the trivial, ready to engulf all that humanity has worked for in a wave of Kardashian botox, an infinite number of X-factor seasons and How I Met Your Mother running jokes. It is a white wash of Rick Rolling Nyan cats, forever alone Salad Fingers, dancing Gangnam Style in chocolate rain with annoying oranges, dreaming of Friday with Rebecca Black who has her pants on the ground while she counts to schfifty five.

The global culture is an apathetic sea of voices, searching for continuous stimulation and distraction. It answers to no one, has no tradition to honour and no allegiance to observe. It values humour and novelty while neglecting responsibility and accountability.

Story well

It is up to us to understand, articulate and celebrate our story that makes us who we are as New Zealanders. We have to be intentional about the points of or history that we want to shape our imaginations looking forward. Maori call this 'pūrākau', story-telling that shapes the root or base of who we are. Stories that we continually tell to preserve what we value in our story so far.

Let's keep telling the story of the nation's response to the Christchurch earthquakes. Keep telling the story of Kate Sheppard acting on behalf of women in a historic move. The story of our men and their heroic bravery at Gallipoli. A story of a nation that has not given up on the struggle to see two cultures embrace without overwhelming each other.

Let us identify ourselves with these shaping events.

Let's tell the story well so that we shape our land with intention for the future. This is harder than amusing ourselves or jumping into popular ways of thinking that the Internet preaches.

But we are worth preserving. We are worth not selling out for convenience.

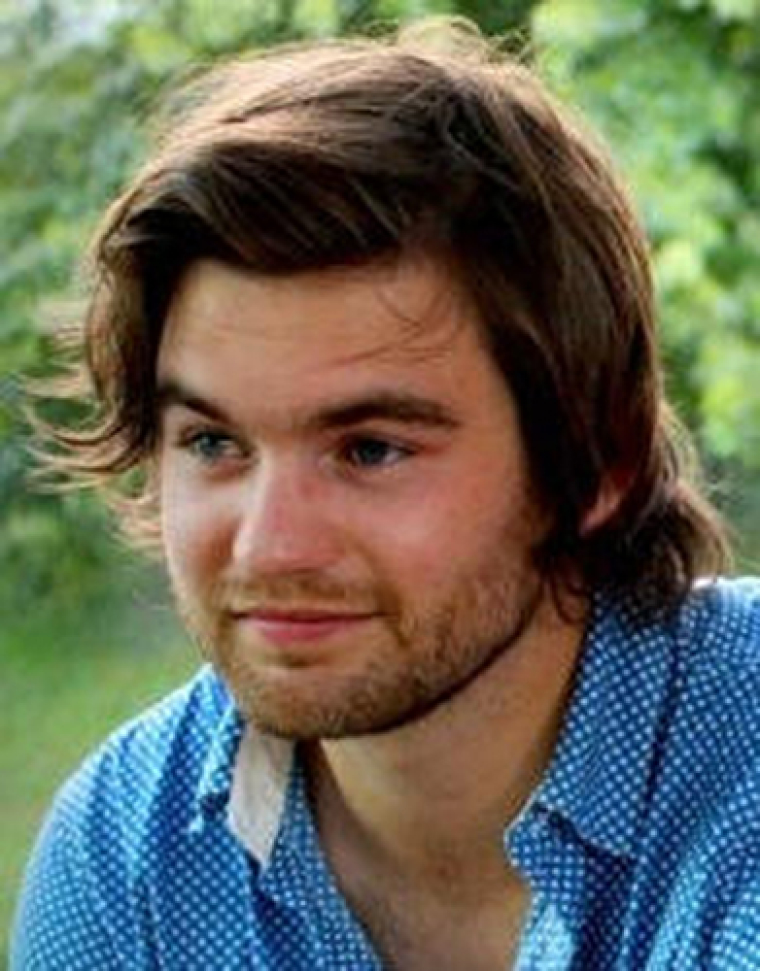

Sam Burrows previous articles may be viewed at www.pressserviceinternational.org/sam-burrows.html