I'm 26 and I can't stop thinking about dying.

I have no real reason for this preoccupation other than a few early grey hairs and a growing tendency to drive my car into stationary objects. Other than that, I would probably have to assume that I'm in my prime and still perfectly fit and available for All Black selection.

But I think about snuffing it all the time, and it's awkward because it seems to be the worst conversation starter at parties and an awful way to impress girls.

But that's just it; for some reason the only sure thing in life (Daniel Defoe obviously hadn't heard of tax evasion) is a taboo subject within the Western world and is ignored accordingly. Dying is seen as a morbid topic to dwell on and should be confined to hospitals, funerals and Eric Clapton songs. Youth is championed, and the myth of the eternal twenty-something living in a carefree L'Oreal commercial is far too pervasive.

But this is a problem, because death is, in many ways, a misunderstood preacher. It thunders an important sermon from the pulpit. And it cannot be ignored, no matter what you believe about life.

Death is the great leveller. It meets us all. It is the fate that we all march towards. And secularism has nothing to say about it, because secularism has been watching too many reruns of the Big Bang Theory even though the series was never funny to begin with.

Secularism seems to have presented a glaringly obvious gaping hole in the conversation around death. It doesn't know what to do with the subject, so in its awkwardness has opted to shoving it deep into a secret cupboard and plastering it over with Marvel posters and inspirational pictures about perseverance, teamwork and positivity.

For Christians, we tend to do our own plastering job, appealing to sentimentalism, vague comments about God's plan and sometimes confused ideas about a three tiered universe in which our loved ones are looking down upon us. It's still awkward even if we do use Christianese.

Tangihanga

Tui Cadigan writes that this has not gone unnoticed in the Maori community. The effects of colonisation have spread through the culture of our country's indigenous people, changing many traditions and ways of seeing the world, but tangihanga, the death ritual has largely gone untouched. Elements have been adapted in the merge with Pakeha culture, but it stands as a relatively unchanged bridge to pre-settler living.

Cadigan notes that although very few Maori attend liturgical services, hundreds will attend a tangihanga – with liturgy and spiritual experiences joined with the rhythms of life. She writes "In death, an air of extreme emotion and spiritual tension is activated when the life force of the person is extinguished and the ritual encounter shifts to the wairua or spirit of the deceased; this is so powerful that it draws people into the drama of death." She goes on to say "In such a heightened state of spiritual connectedness, in which God is being addressed repeatedly, the secular world is deemed subordinate."

This is a telling assessment.

This trend is just as accentuated among other cultures within New Zealand. We are happy to carry on with our self-sufficiency and lifestyle chasing patterns of living until the myth is exposed, and we see that we have always been fragile creatures, clambering after significance to rescue us from our mortality. Ever running from our own tangihanga. Living in denial.

If death presents a gaping hole in society's rhetoric about life, then this is an opportunity to expose it and have the doors and windows open to God. There is something frighteningly charged about staring death right between the eyes, and the biochemical speak of secularism cannot capture this in the language of entropy and system failure. Death is the megaphone of the miracle of existence, and it must get more air time.

The Sermon

So what is the message? Well, death brings life itself into sharp focus. It rids us of the superfluous.

Two years ago a good friend of mine was diagnosed with liver cancer and died at the age of 22. Two months before she passed away I had dinner with her and got to hear what it was like to see life from her new vantage point. I expected confusion, possibly a bit of anger, perhaps disappointment and certainly fear. She didn't talk about any of those things.

She told me that she was thankful that she had been chosen for the task, because of what was being achieved through her experience in the lives of others and because of the love she was receiving amongst it. She told me that now she was in the position she was in, life was all about what she could give in the time that she had left. I don't think I've been the same since that conversation. Perhaps in death you learn that this was the nature of life all along. A fleeting chance to love well. Perhaps we learn that 2000 years on we still haven't learned that to truly save our lives, we must lose them.

Maybe 'evangelistic' conversations shouldn't start with "If you died tonight, do you know where you'd go?" but rather, "Ever pondered the miracle of your existence?"

William Law said 'If you attempt to talk to a dying man about sports or business, he is no longer interested. He now sees other things as more important. People who are dying recognise what we often forget, that we are standing on the brink of another world.'

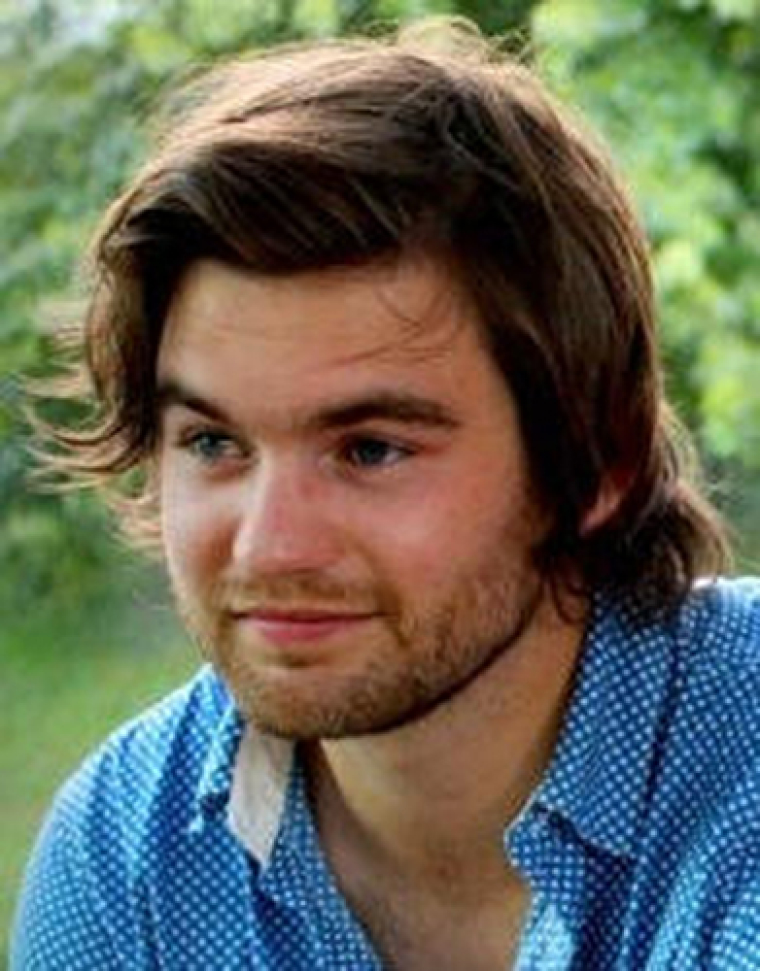

Sam Burrows previous articles may be viewed at www.pressserviceinternational.org/sam-burrows.html